It’s been a tumultuous twenty years for fans of Clive Barker. Ever since the visionary horror author and acclaimed cult film director teased a new adventure for his most famous character in 1993, devotees of the lead Cenobite Pinhead have been waiting on, well, pins and needles to see if The Scarlet Gospels would ever come to fruition.

Take that, impatient George R. R. Martin fans! It could get worse!

The last two decades have seen Barker tackle dark fantasy novels including Abarat and Coldheart Canyon, launch an action figure line, write comics, direct his third movie, Lord of Illusions, and become a prolific visual artist. He’s also struggled with some very serious health problems, including a near-fatal case of toxic shock syndrome last year.

It goes without saying that expectations for this long-awaited novel are extremely high. Only, I wasn’t one of the people waiting for this novel. Not exactly.

I love my fiction dark and weird, and so I list Clive Barker as one of my all-time favorite writers. I’ve read and re-read his collected short stories. The Books of Blood is subversive, imaginative, violent, sexual, sensual, memorable— a landmark single-author anthology. Barker was one of the first openly gay authors I’d ever read and his stories were definitely the antithesis of the kind of lurid novels one could find on a spinner rack at a supermarket back in the day. The flip side of Stephen King’s suburban horrors, if you will.

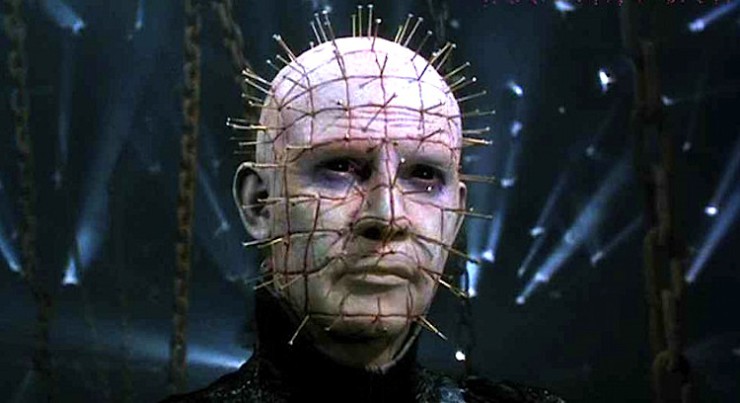

1986’s The Hellbound Heart is packed with so much horrific beauty, tension, and lyrical deftness, it’s impossible to put down. It’s here that the character who would become known as Pinhead made his formal debut in pop culture. In the novella, he had no name, he was “just” the leader of The Order of the Gash, a gender-ambiguous, poetry-spouting demon from Hell that specialized in sadomasochistic torture of the world-weary, unlucky people who opened the rare puzzle box that was the Order’s calling card.

After the success of the novella, Barker returned to his other love—film—and directed the first Hellraiser feature. The rest was Hollywood history: Pinhead and his distinctive facial scars were added to a pantheon of less eloquent cinema baddies that included Michael Myers and Freddy Krueger. The inevitable sequels racked up in numbers but diminished in quality, as Barker’s involvement in them was as a producer only.

One can understand why Barker would want to clear Pinhead’s name and breathe new life into his franchise with The Scarlet Gospels.

About that name? Pinhead? Don’t use it.

It’s an insult to a creature that is ancient, powerful, and full of a dark ambition to make all of Hell—right up to the Father of Lies—beg for mercy.

There is much that Barker gets right in his latest novel and that is primarily his vision of Hell. This is not Dante’s nine circles. Hell’s capital city is instead a dark mirror of Rome: eight hills, tree-lined streets, and fantastical statues.

“And everywhere the laws of physics were casually defied: an immense building was held a hundred feet in the air or more by the two steep rows of steps at the front and the back; a trio of pyramids, their squares intricately inscribed, were built so as to seem caught by a seismic jolt…”

Hell is a vast country under a sky capped with stone. There are deserts littered with broken machinery, lakes populated by sea creatures, deadly forests, and many different tribes of demons, angels, and the damned. Barker brings a painter’s skill to this window dressing. His representation of Lucifer was also really intriguing and I would’ve enjoyed more time with him.

Sadly, I wish I could say I was as satisfied with the brushstrokes used to create The Scarlet Gospels’ human characters. A certain narrative distance from the Hell Priest is expected; he’s the antagonist dogging the main human character, he’s practically divine and thus impossibly unknowable and he’s working towards a secret agenda whose endgame isn’t clear to the reader until… the very end. Same with Lucifer.

My larger disappointment was with all of the human characters who existed only to be tormented by Pinhead.

The opening prologue is comprised of four whole chapters of pretty much straight-up torture, including the rape and forced pregnancy of a female magician in a group of people we just met. I get that Pinhead’s business is torture, but protracted gruesomeness over such a long scene right at the start of the novel was supremely off-putting. Then it became downright tedious. I think that was worse.

My interest perked up more once the meat of the story was finally introduced.

Detective Harry D’Amour is arguably Barker’s second most-famous character, having short stories (“The Last Illusion,”) novels (Everville,) and a movie of his own (Scott Bakula portrayed him in Lord of Illusions.) An occult detective, Harry is a walking encyclopedia of private eye tropes: world-weary, cigar chomping, a lover of the drink, he has a dead partner, he has friends in weird places, etc. This isn’t to Harry’s detriment; Richard Kadrey’s Sandman Slim and Jim Butcher’s Harry Dresden haunt the same seedy underbellies in their own cities. I could see the three of them hanging out, exchanging witticisms.

When Harry catches the black eye of Pinhead, the Hell Priest wants Harry to bear witness to his atrocities and so kidnaps Harry’s oldest friend, an elderly clairvoyant named Norma, to bait the detective into traveling to Hell. While Harry’s concern for the old woman is touching, we really don’t get to see much of what drives Harry to continually throw himself into the paths of monsters and mysteries beyond being a decent but unlucky guy.

Harry’s misfit friends who join him on the diabolic ride are even more one-dimensional. As their rescue mission goes haywire, I thought there would be a Ten Little Indians-style thinning of the herd through ironic deaths related to character flaws—a very Hollywood thing in horror—but, nope, they’re just hangin’ out and cheerleading for Harry. In Hell. We never learn enough about them to discover any weaknesses the Hell Priest could have exploited, so their quippy banter just distracted from Harry’s quest.

Personally, I would’ve been happiest with a sequel to The Hellbound Heart that maintained the original novella’s thematic elements and near-hypnotic prose that could so easily show the beauty in even the darkest of horrors. But Barker hasn’t written like that in a very, very long time and I knew it.

The Scarlet Gospel is more of a sequel to the Hellraiser movies—the tongue-in-pierced cheek references to the Hollywood version of a Hell Priest, the funny little Easter eggs revealing the fates of some of his Cenobite buddies, and callbacks to some of the film’s famous lines. This novel is also more of an epic fantasy framed in a contemporary urban adventure; while horrific things happen (including another rape thrown in as almost a cruel afterthought) I wouldn’t call this a horror story.

Fans who have been waiting two decades for The Scarlet Gospels will likely pick it up regardless of any negative reviews, and if you’ve really been that into all things Hellraiser, this book might not disappoint. Clive Barker’s imagination remains one of the genre’s brightest, but hopefully those other long-suffering Barker fans who are still waiting for the next book in his more recent and more vibrant Abarat series won’t have to wait so long and will receive much better. Then there’d really be hell to pay.

The Scarlet Gospels is available now from St. Martin’s Press.

Theresa DeLucci is a regular contributor to Tor.com, covering book reviews, gaming news and TV, including Game of Thrones. She’s also discussed entertainment for Boing Boing. A student of the 2008 Clarion West Writers’ workshop, her short fiction has appeared in ChiZine. Follow her on Twitter.

I got a chance to review this back in March, and I really enjoyed it. I felt the writing/style/narrative was vintage Barker, but I really do wonder what could have been if we’d gotten the full novel he teased for so long.

At one point, Barker promised it to be a massive 232,000 word epic, but it got edited down to less than half that size. So many scenes and ideas he’d teased were left on the cutting room floor, denying us the epic feel ofa novel like Weaveworld or Imajica, and (I suspect) eliminating a lot of the human character development.

Your review was well-written and i can see where you’re coming from. It was missing that little extra stylistic flair that made me love Barker so much originally. My favorite chapters, the ones that felt most authentic to me, were from Pinhead’s POV. (Those origami birds! So cool. Reminded me of Barker’s pre-Hellraiser short films.) I really didn’t think Harry and Pinhead interacted enough. I think I would’ve enjoyed the weirdness of it all if everything were from Pinhead’s perspective.

Stupid humans, ruining everything as usual… Heh.